Entry #6

When my husband, Gary, and I married over 30 years ago, it was only natural that I would take an interest in his family history, especially since I was adopting the surname “Hartley” as my own. Someone in the family had already made a nice start on the family tree, which was a big help to my later endeavors. One of the interesting family stories was that William and Martha Hartley, Gary’s 3x great-grandparents, had died in Melbourne, Australia. It was told that they emigrated from Yorkshire, England, to Victoria in 1858. Since their youngest son, Frederick, had relocated from Yorkshire to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1853, this stood out as a bit of an anomaly. I asked myself the question, why would a couple, each in of them in their sixties, take up a new life in such a distant and difficult land? They already had at least one son in America. I fully expected to find that another child had emigrated to Australia and thought I’d find one of Frederick’s siblings in Melbourne. It took years of research before a very different story unfolded.

William Hartley was born on September 14, 1794, in Thornton, near Bradford, England. His father, Thomas Hartley, and his mother, Hannah Charnock Hartley, were the parents of at least six children. They were Methodist and members of Kipping Independent Wesleyan Chapel in Thornton. William married Martha Sutcliffe on February 20, 1814, in Bradford Cathedral. All persons practicing a Non-Conformist religion, as they did, were required to have their marriages solemnized by the Church of England. William and Martha had six children in 17 years. Frederick, my husband’s great, great-grandfather was the last child, born in 1831. Most of my husband’s family were weavers by trade, but for some reason, William Hartley entered the profession of stonemason.

As one might expect, I used the 1841 and 1851 censuses as tools to help reconstruct their lives. I was thrown by what I discovered. I could not find William and Martha together in either census, so I decided to look for Frederick. It was easy to find Frederick in the 1851 census along with his widowed mother, Martha, living in Horton. Frederick’s future wife, Mary Ann Hainsworth, was enumerated in the household as a “visitor,” so there was no doubt I had found the right family.

1851 Census for Great Horton Source Citation Class: HO107; Piece: 2310; Folio: 10; Page: 13; GSU roll: 87524-87525

Wait a minute…Martha was a widow? Was the family story about William and Martha dying in Australia a myth?

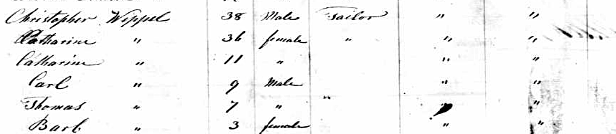

I backtracked to 1841 and found Frederick Hartley in Thornton in the household of James Garth and there was Martha…Martha Garth to be precise. Right next door was Joseph Hartley, William’s youngest brother.

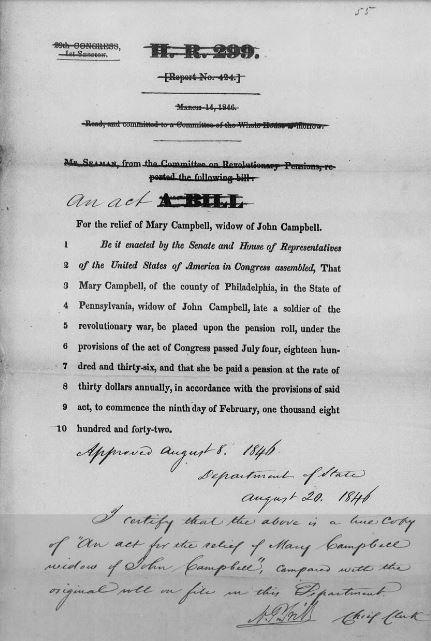

![Martha Garth in 1841 Census for Thornton - Source Citation Class: HO107; Piece: 1297; Book: 7; Civil Parish: Thornton; County: Yorkshire; Enumeration District: 4; Folio: 6; Page: 4; Line: 14; GSU roll: 464257 Source Information Ancestry.com. 1841 England Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc, 2010. Original data: Census Returns of England and Wales, 1841. Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives of the UK (TNA): Public Record Office (PRO), 1841. Data imaged from the National Archives, London, England.](https://mysearchforthepast.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/martha-hartley-1841-census-pg-2.jpg?w=211)

Martha Garth in 1841 Census for Thornton – Source Citation

Class: HO107; Piece: 1297; Book: 7; Civil Parish: Thornton; County: Yorkshire; Enumeration District: 4; Folio: 6; Page: 4; Line: 14; GSU roll: 464257

Another search uncovered a marriage record for Martha Hartley and James Garth. Martha was a “widow” at the time of her marriage.

Marriage James Garth and Martha Sutcliffe Hartley – West Yorkshire Archive Service; Wakefield, Yorkshire, England; Yorkshire Parish Records; Old Reference Number: 40D90/1/3/17; New Reference Number: BDP14

I could have stopped looking there, but the family story seemed credible; it even included an address – 80 Rose Street, Fitzroy – a neighborhood of Melbourne. At this point, I decided to look for records in Melbourne. I was able to find William Hartley in the Melbourne city directories for multiple years. Later, I found listings for Martha, widow of William.

Where was William during all the missing years? In one of my searches I came across a William Hartley of Ovenden who was convicted of trying to pass forged bank notes. Could this possibly be the same William Hartley?

From the calendar of felons: Hartley, William, age 38, Ovenden, 27 August 1832:

William Hartley, late of Ovenden, in the west-riding, builder, charged on the oaths of William Brigg, and others, with having in his possession, at Bradford, in the said riding, on 25th day of July last, two forged and counterfeited bank of England notes, purporting to be notes of the Manchester branch of the bank of England, for payment of five pounds each, with intent to utter the same.

Guilty of feloniously having in his possession a forged bank of England note – to be severally transported beyond the seas for the term of fourteen years.

William, it seems had gone to the Royal Oak Inn to try to change his bogus notes, but the Constable and his deputy were waiting for him. During the arrest, William tried to swallow the forgeries, but the law managed to restrain him from destroying the evidence!

William Hartley – Leeds Intelligencer September 06, 1832

It is possible that William was a repeat offender. He was described as belonging to a “bad gang.” William Hartley was transported on the ship Surrey on November 19, 1832, and arrived in Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) on April 7, 1833.

The Convict Ship Surrey

The Convict Ship Surrey

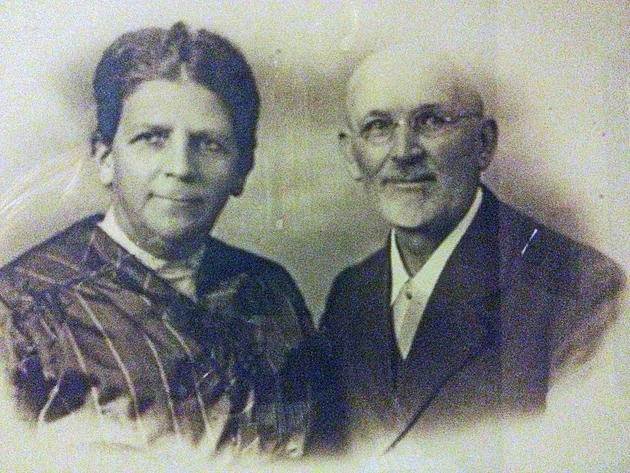

I wrote to the archives in Victoria and received an entire packet consisting of William Hartley’s convict file. It named his wife, Martha, and mentioned his children. At that point, the story became clear. Gary’s great, great, great-grandfather was an Australian convict!

The convict files tell us a lot about William, including a physical description, which was provided for each convict. At age 36, William Hartley was 5 feet, 6-1/2 inches tall with a dark complexion, hazel eyes, brown hair and dark red whiskers. He was described as having an oval head with dark brown eyebrows on a low, retreating forehead. His nose was “sharp,” his mouth “M.W.” and his chin “large.”

William was sentenced to hard labor on the road. He ran away several times “to work for himself.” He was sometimes drunk. Despite this, William was given a ticket of leave on April 26, 1842. Finally, he received his certificate of freedom (often referred to as a “pardon”) in 1846.

William was sentenced to hard labor on the road. He ran away several times “to work for himself.” He was sometimes drunk. Despite this, William was given a ticket of leave on April 26, 1842. Finally, he received his certificate of freedom (often referred to as a “pardon”) in 1846.

William Hartley did not return to England. It isn’t known yet what William did immediately following being freed, but around 1849 he moved on to Victoria. By 1857 he had became a freeholder on Rose Street in Fitzroy, Melbourne, where he remained until his death. There are lots of minor details left to fill in. There was a William Hartley of Fitzroy who was charged with operating an illegal still. He was acquitted. Was this Gary’s forebear?

William Hartley did not return to England. It isn’t known yet what William did immediately following being freed, but around 1849 he moved on to Victoria. By 1857 he had became a freeholder on Rose Street in Fitzroy, Melbourne, where he remained until his death. There are lots of minor details left to fill in. There was a William Hartley of Fitzroy who was charged with operating an illegal still. He was acquitted. Was this Gary’s forebear?

In 1858 Martha Sutcliffe Hartley joined William on Rose Street after a presumed separation of 26 years. It is not clear as to the circumstances of the reunion. Did William write to Martha and ask her to come to Australia, or did she make the trip without advance notice? Martha traveled on the Oceanica, classified on the ship’s passenger list as a “spinster.” After years of calling herself a widow, it is strange that she represented herself as being single. Was she keeping her options open in case William did not welcome her with open arms? At any rate, William and Martha Hartely spent their final years together. William died in Melbourne on November 26, 1874. Martha died in 1880.

The family legend was almost true. William and Martha did both die in Australia. The family just chose to forget a few minor details about forgery and bigamy.

Source Information:

Ancestry.com. 1841 England Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc, 2010. Original data: Census Returns of England and Wales, 1841. Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives of the UK (TNA): Public Record Office (PRO), 1841. Data imaged from the National Archives, London, England.

Ancestry.com. 1851 England Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005. Original data: Census Returns of England and Wales, 1851. Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives of the UK (TNA): Public Record Office (PRO), 1851. Data imaged from the National Archives, London, England.

Ancestry.com. West Yorkshire, England, Marriages and Banns, 1813-1935 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original data: Yorkshire Parish Records. West Yorkshire Archive Service: Leeds, England.

![Martha Garth in 1841 Census for Thornton - Source Citation Class: HO107; Piece: 1297; Book: 7; Civil Parish: Thornton; County: Yorkshire; Enumeration District: 4; Folio: 6; Page: 4; Line: 14; GSU roll: 464257 Source Information Ancestry.com. 1841 England Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc, 2010. Original data: Census Returns of England and Wales, 1841. Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives of the UK (TNA): Public Record Office (PRO), 1841. Data imaged from the National Archives, London, England.](https://mysearchforthepast.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/martha-hartley-1841-census-pg-2.jpg?w=211)