This week the optional theme for 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks is “Challenging.” I guess that is one of the things that I enjoy about genealogy – the challenges. Truly, it wouldn’t be any fun for me if the ancestor quest didn’t include endless mysteries to be solved.

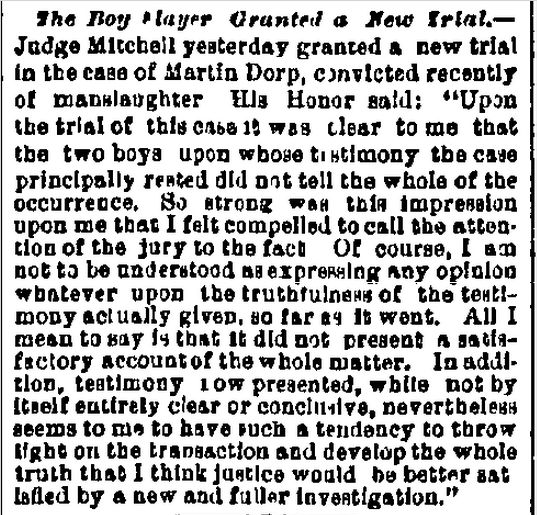

Sometimes family history is intuitive and, even, serendipitous. I am not saying that one shouldn’t practice good research habits, but there are also times when one feels the urge to follow a hunch. That was the case with Anton Stephan, my 2nd great-grandfather. I started my search for him with no information except the names of his children. When I began, I knew that my great-grandmother, on my maternal grandmother’s side, was Julia Stephens from Ripley, Brown County, Ohio. I had no information about her parents, although I assumed they were German. My parents used to play at arguing about who was more German. My dad would say to my mom, “What about your grandmother? Her name was Stephens and that’s English.” My mother would explode, “English! She wasn’t English!”

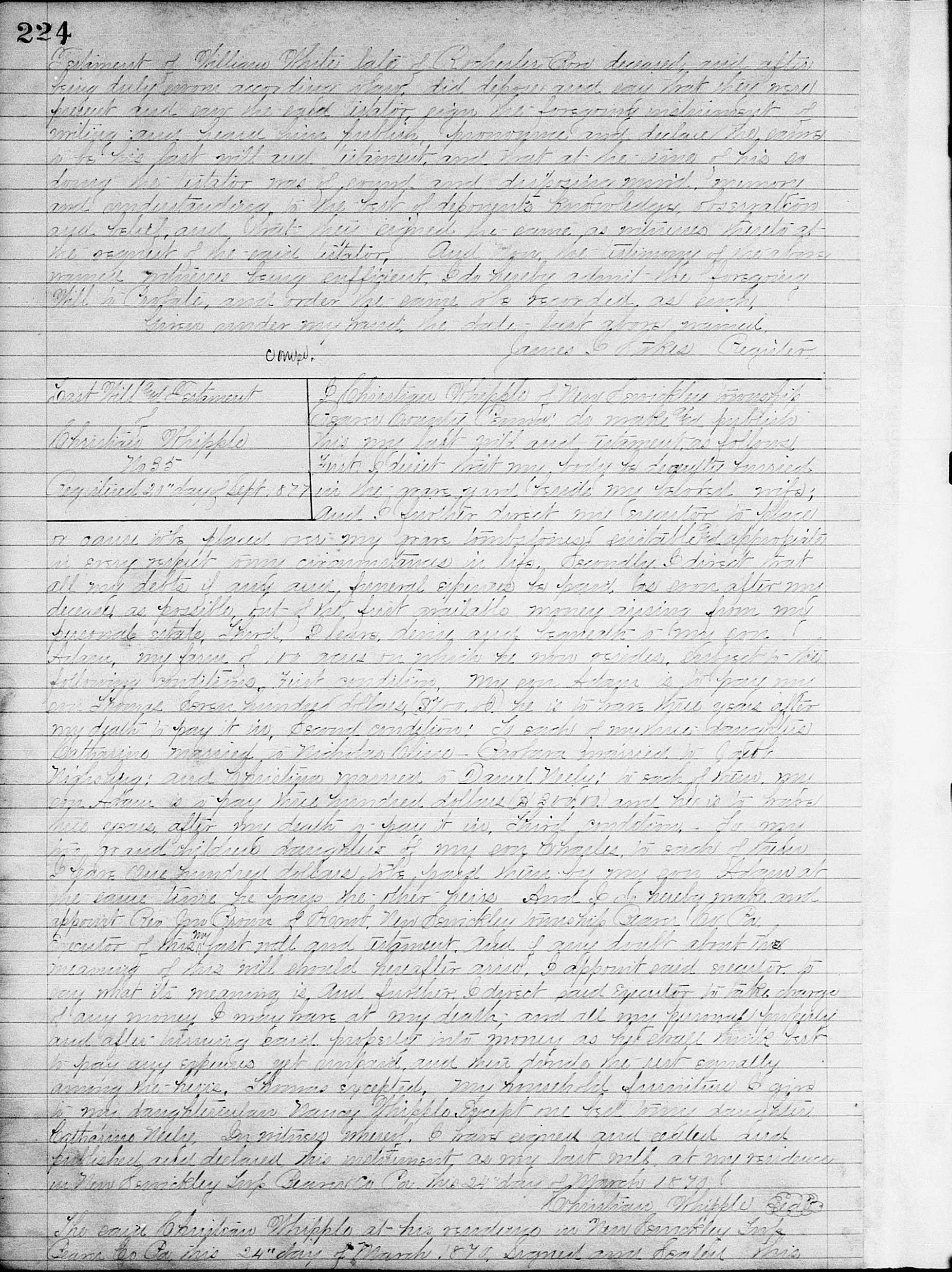

Julia wasn’t too hard to find in the 1860 U.S. census, though; from there, I learned that her parents were Anthony and Catharine Stephen and they were, indeed German (even though, in the 1860 census, Catherine was mistakenly identified as having been born in Ohio). I found this information 15 or more years ago.

Julia was born in 1856, and the census listed her older sisters and a brother. I was familiar with this family through the stories of my aunt and my mother. The census matched what I had heard through oral history, including the documentation of a brother who was believed to have drowned.

![Online publication - Ancestry.com. 1860 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. Images reproduced by FamilySearch.Original data - 1860 U.S. census, population schedule. NARA microfilm publication M653, 1,438 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d. Eagle, Brown, Ohio, post office , roll , page , image .](https://mysearchforthepast.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/anton-stephan-1860-census-extract.jpg?w=300)

Online publication – Ancestry.com. 1860 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Images reproduced by FamilySearch.- 1860 U.S. census, population schedule. NARA microfilm publication M653, 1,438 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d. Eagle, Brown, Ohio, post office , roll , page , image .

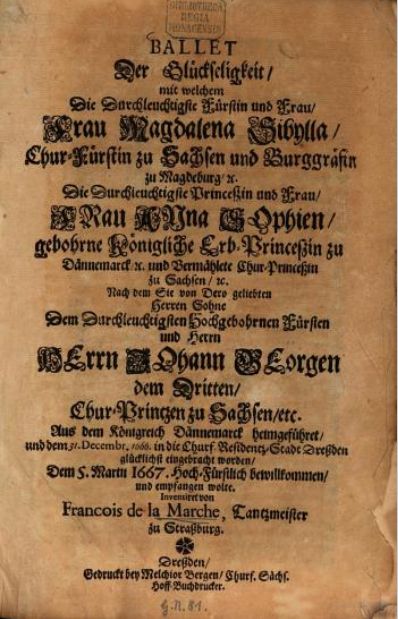

I hunted for Anthony and his family in the 1850 census and couldn’t find them at first. These were the early days of Ancestry.com and search engines were less sophisticated. Anton was transcribed as “Inton Stepan” and the family was living in Mason County, Kentucky; but he was shown in the household above the rest of the family, which I presume was a mistake. It was no wonder that the name wasn’t transcribed properly. The writing is faint and difficult to read. Eventually, I realized that the correct name for my ancestor was Anton Stephan (the German spelling).

Year: 1850; Census Place: District 1, Mason, Kentucky; Roll: M432_212; Page: 30A; Image: 401

Search as I might, I could not, and never have found my Stephan family in the 1870 census. I thought, perhaps, Anton had died before 1870. I located several of the adult children in Cincinnati and other locales by 1880. Gradually, I found other records for my great-grandmother Julia (whose real name was Juliana Magdalena Stephan), but who was also alternately known as Julia, Lena and Maggie through the course of her life. Death certificates and burial records gave me the name of her mother as Catharine Helfrich. While I didn’t have names for Catharine’s parents, I had a hunch. There were two Helfriches, Francis and Anna Otillia, living in Brown County contemporaneous to Catharine Helfrich Stephan residing there. Could Otillia be Catharina’s mother? She was the correct age. Francis (sometimes “Frank”) was too young to be her father, though. Maybe he was a brother, or perhaps his age was wrong in the census. It was confusing, but I added these people to my family tree without postulating a relationship to me.

The 1850 census indicated that the oldest two children were born in Germany in 1848. That told me that Anton and Catharina must have immigrated in 1848-1849, since they appeared in the 1850 census. I also had information that showed the Stephan family came from Bavaria. Bavaria was a huge place, though, and I couldn’t find this family on a ship’s passenger list. How would I ever find the birth place for Anton or Catharine?

And, that is where I got bogged down…

For years, I couldn’t find any more information. I spent a lot of time searching for Stephan and Helfrich records. Stephan is a very common German surname, but Helfrich is a little more narrowly distributed. It seemed likely that my family originated in western Bavaria.

Surname Map for Helfrich – Courtesy of Christoph Stoepel

There was a marriage for an Anton Stephan and a Catharina Helferich in Leiman, Pfalz, Bavaria, but it took place 14 January 1800. My Anton Stephan was not born until 1810 or 1811. Still, this was interesting and I wondered if they were relatives. Sometimes families would be allied over many decades. Maybe these were Anton’s parents. It was even possible that Anton married a cousin with the same name as his mother.

Still, I did not feel confident enough to pursue ordering the LDS films for Leiman. I continued searching. Eventually some more records turned up for the couple that married in 1800. At least I thought it was them. These were marriage records for their children and the church was in Munchweiler, Piramasens. There was no Anton that would have been a good fit for mine.

More and more, I felt as though I was being pointed to the Pirmasens area of the Southwest Pfalz. I located the Pirmasenser Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Familienforschung or Pirmasens Genealogical Study Group It is so helpful that they have an English version of their website. Here I discovered emigrants from the Pirmasens area. Anton Stephan was not listed, but I found a number of people who left and settled in Brown County, Ohio. It was looking more and more positive that my Stephan family came from somewhere in the area.

About five years ago I had a breakthrough when I found Anton Stephan listed by Find-A-Grave. There was even a photo of his tombstone and dates of birth and death! Now, I finally had something a bit more concrete. His date of birth was 30 January 1811 and he died 2 May 1871. (Again, I realized, he should have been enumerated in the 1870 census. I still cannot find him.)

Find-A-Grave; Maplewood Cemetery,

Ripley, Brown County,

Ohio, USA; Added by Paul (Dakota) S

Armed with dates, I began to search further. I found several online trees that had an Anton Stephan from Eppenbrunn near Pirmasens. His date of birth was 29 January 1811. Could this be the same person as my great, great-grandfather? There was a problem, though, besides the birthday being off by one day. There was a family tree that recorded this Anton Stephan as having died before adulthood. I decided not to be discouraged; we know that there are mistakes in a lot of family trees.

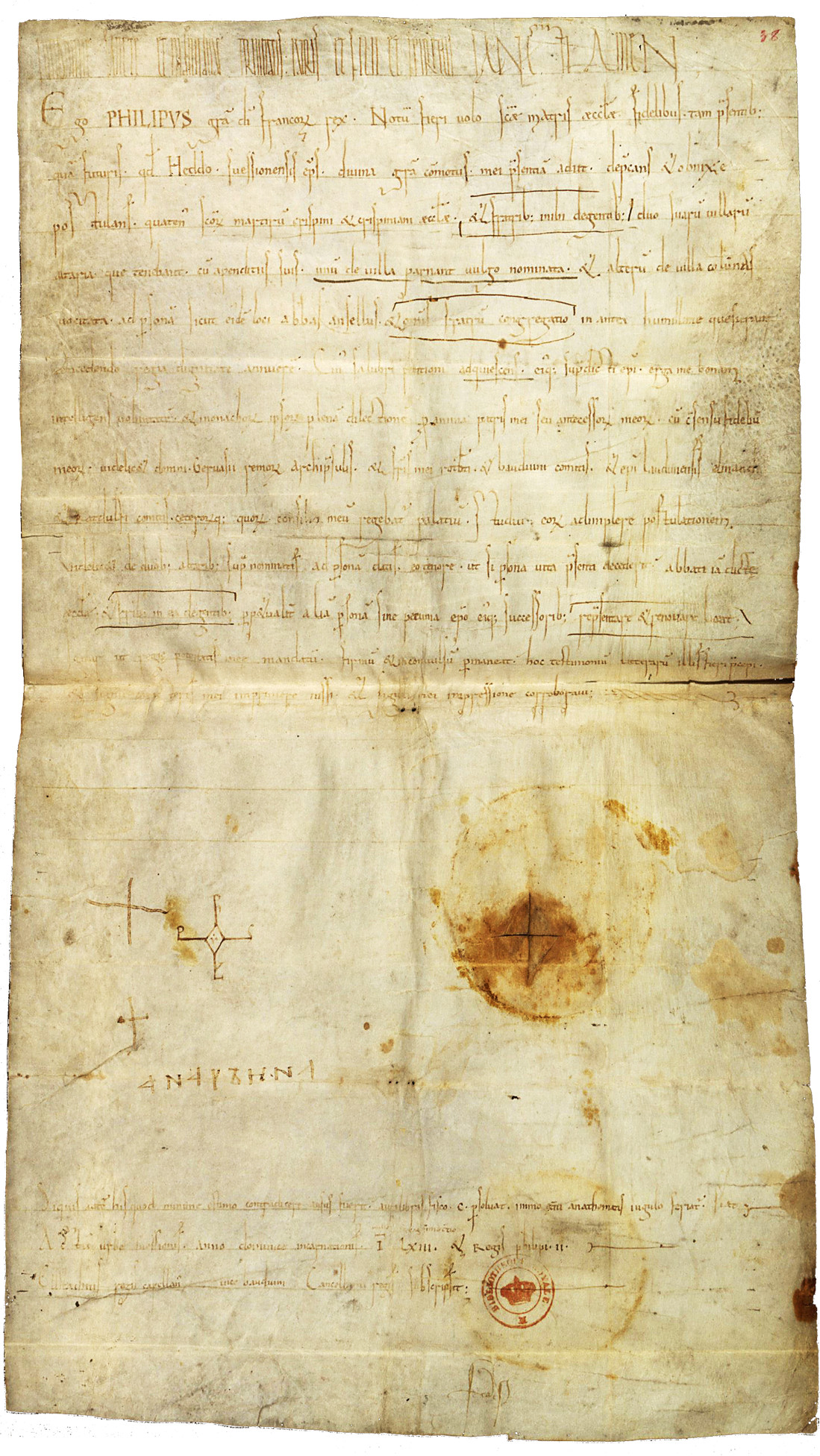

A little over two years ago, I tested my autosomal DNA at Ancestry.com. Darn, there were no verifiable Stephan matches in the beginning; but there were matches who had ancestors in Eppenbrunn and another in a nearby town called Vinningen. I finally felt that it was time to test my hunch. I would try to verify that my Anton Stephan and the one born in Eppenbrunn were one and the same. I also noticed that the surname Helfrich was found in Vinningen. I ordered Catholic church films from the parish of Trulben, which included Eppenbrunn; I decided to look at Vinningen, too, and ordered those records.

The Trulben film was partially indexed and I easily located Anton Stephan’s christening record. Yes, I had found him! I was so excited. He was the son of Jean Stephan and Elisabeth Gehringer. Then, I began looking for the marriage to Catharina Helfrich. It wasn’t there; nor, did I find her baptism record in either Vinningen or Eppenbrunn. Well, I thought, at least I found Anton Stephan.

Taufen 1797-1823; Heiraten, Tote 1808-1823; Family History Library International Film 400500; Katholische Kirche Trulben (BA. Pirmasens)

On my hour and a half drive home from the Family History Center in Sissonville, West Virginia, it dawned on me. I had proven nothing. All I did was confirm that the Anton Stephan in the Eppenbrunn christening record was the same one that I had found in other trees. The proof that this was my Anton Stephan lay in finding the marriage to Catharina Helfrich and I had not been able to do that. I had just been a victim of my own circular argument!

Oddly, while I was scouring the Vinningen film for Catharina Helfrich, I found something else of interest. I found a baptism record for Peter Elsässer. I copied the record because I have two close DNA matches who have the same Peter Elsässer as a common ancestor. The date of birth didn’t match, but it was close.

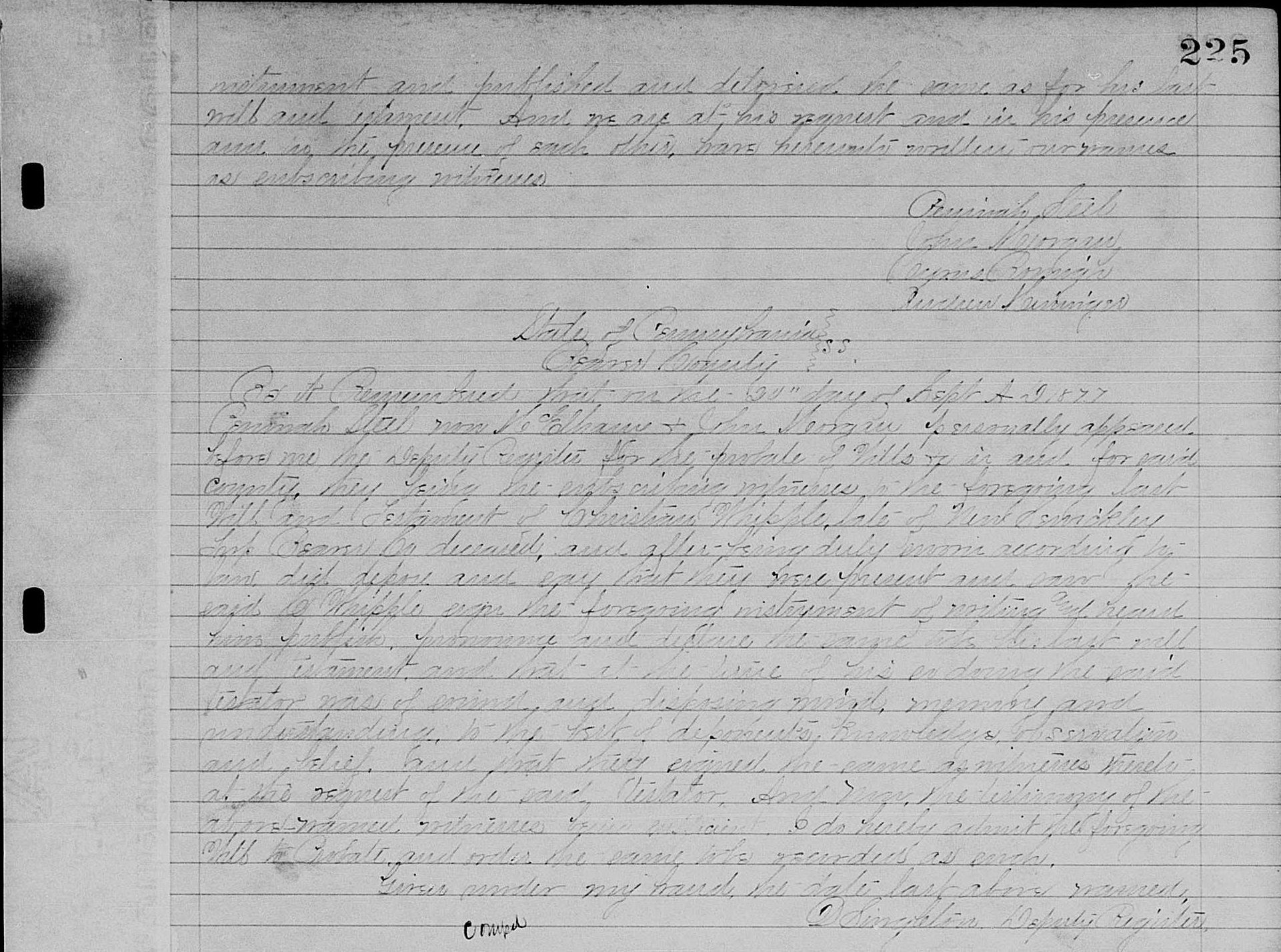

I decided that I needed to get grounded and make sure that I hadn’t missed any clues in the United States. I still felt strongly that I had found my ancestor, but I just hadn’t proved it. Something I still needed to do was to hunt down the will of Frank Helfrich. I have written about this before. This is where I found a stunning revelation. Frank Helfrich made his stepdaughter his sole heir. Her name? – Catharine Stephan, wife of Anthony Stephan. Catharine’s name at birth had not been Helfrich, but what had it been? I needed to know her maiden name to find my proof for Anthony.

I posted to the Brown County Facebook group about my dilemma. In no time at all, Lynn Wayson Koehler shared a marriage record from FamilySearch.org with me. It was for Anthony Stevens and Catharnie (sic) Elcesser on 3 May 1846. My heart did a flip-flop. Here were my 2nd great-grandparents and they had married in Brown County.

Stephan – Elcessor Marriage – Brown County Ohio

I tried searching, but could not find the same record; however, using the date of the marriage it was not difficult to locate. My real shock, of course, was that the name Elsässer had turned up. I already knew that there were Elsässors in Vinningen. I couldn’t wait to return to the Family History Center to look for them.

I found Catharine Elsässor’s christening record and it fit her projected age. She had grown up a mere 7 kilometers from Anton. I won’t go into all the details, since I have posted on the Elsässer findings here.

This still didn’t definitively prove that the Anton Stephan from Eppenbrunn was the one I was seeking. But I was stacking up evidence to support my hunch that he was. For one thing, there was no death record for Anton in Eppenbrunn, nor in the surrounding communities; further, there was no marriage record for him there. Anton Stephan appears to have vanished (and that was a good thing!) He may have emigrated to the United States as early as 1837. A ship’s passenger list for New Orleans has an Anton Stephan who was the right age arriving in 1837.

Finally, I decided to return to the DNA. I had now filled out a tentative tree for Anton and had more surnames that I could test with my matches. I had great results. I have two matches who document their ancestry to my 6th great-grandparents, Johannes Nikolaus Roth and Johanna Mistler, a branch of my Stephan line. I also have Gehringer matches that link me to Anton’s mother. Further, my aunt and sister have since tested their autosomal DNA. They, too, have matches supporting the theory that the Anton Stephan of Eppenbrunn is, indeed, our ancestor.

This was a long and complicated search, but one that was very rewarding. Along the way, another family researcher advised me not to waste my money on renting the Eppenbrunn and Vinningen films. I am glad I didn’t listen. I know a lot of my research was based on a feeling in my gut that I was on the right path, but I think that each step was measured and tempered with reasonable conjecture. After all, if you are going to prove something, you must first create a hypothesis and then test it. That is really exactly what I did.

![Online publication - Ancestry.com. 1860 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. Images reproduced by FamilySearch.Original data - 1860 U.S. census, population schedule. NARA microfilm publication M653, 1,438 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d. Eagle, Brown, Ohio, post office , roll , page , image .](https://mysearchforthepast.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/anton-stephan-1860-census-extract.jpg?w=300)